For almost two thousand years, Babylon was one of the most important cities in ancient Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in present-day Iraq. If you combine the economic vitality of New York, the political power of Washington, D.C., and the religious significance of Jerusalem today, you’ll get a sense of Babylon’s stature in the biblical world. Compared to Babylon, Israel and Judah were the sticks—interstate stopovers, so to speak, like Effingham, Illinois, or Wendover, Utah.

What do the Babylonians have to do with the Hebrew Bible?

The Hebrew Bible mentions Babylon more than 280 times. To understand this prominence, you need to know something about Babylonian history and culture.

Situated on the Euphrates River, Babylon rose to prominence under King Hammurabi in the eighteenth century B.C.E. Although Babylon’s political fortunes varied over the centuries, the city remained an important religious center and icon of Mesopotamian culture throughout its long history. Its name became synonymous with the southern region of Mesopotamia (Babylonia).

Although important earlier, it was not until the late seventh century B.C.E., under Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562 B.C.E.), that Babylon became the capital of a vast empire stretching the length of the Fertile Crescent. Within decades, Babylon fell to the Persians under Cyrus (in 539 B.C.E.), but the city continued to flourish. When the Greek king Alexander took Babylon from the Persians in 331 B.C.E., he planned to make it his Asian capital; only his untimely death prevented this. The city lost its luster under Alexander’s successors, the Seleucids, and fell to the Parthians in 141 B.C.E. Its ruins presently lie about 60 miles southwest of modern Baghdad.

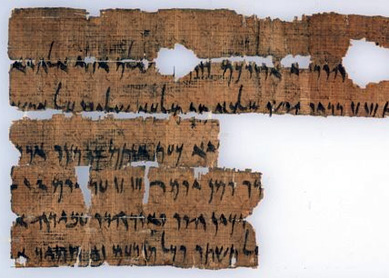

Thousands of cuneiform tablets from Babylonia (and Assyria, its northeastern neighbor) preserve ancient texts that illuminate the biblical world. Enuma Elish, the Atrahasis Epic, and the Epic of Gilgamesh offer parallels to the creation accounts and flood stories in Gen 1-11. Ritual tablets describe the Babylonian process of “making” a god from wood and introducing him into his temple (compare Isa 44:9-20). Babylonian prayers recall biblical psalms, depicting familiar religious concepts (such as sin and reconciliation) and practices (for example, prostration and hand raising). Babylonian tablets also provide evidence for ancient scribal techniques of editing, adapting, and copying traditional texts. This sheds light on how biblical scribes would have produced the Bible.

Why did the Babylonians destroy Jerusalem and exile its people?

The Hebrew Bible presents the Babylonian exile as a theological issue: Judah broke the covenant with its god, and exile was their punishment (see Lev 26:27-39; Deut 28:58-68; 2Kgs 17:19-20, 2Kgs 24:1-4). It also depicts the exile as the result of several political miscalculations on the part of Judah’s leadership during its final decades (2Kgs 23-25).

In the late seventh century, the Judean kings found themselves in the middle of a political hornets’ nest. Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, had fallen to the Babylonians and Medes in 612 B.C.E., freeing Judah from Assyrian rule. In 609, the Egyptians rushed to support Assyria in their final stand in Syria. Josiah (640–609 B.C.E.), Judah’s king, was eager to see Assyria’s final demise, so he tried to block the Egyptians’ route at Megiddo; but the Egyptians killed him (2Kgs 23:29-30; 2Chr 35:20-24). Suddenly, Egypt was calling the shots in Judah.

The Egyptians took the kingship from one son of Josiah, Jehoahaz, and gave it to another, Jehoiakim (ruled 609-598 B.C.E.), who became their puppet (2Kgs 23:33-35). But Nebuchadnezzar defeated the Egyptians in 605 B.C.E. at the battle of Carchemish and took control of Syria and Judah. Jehoiakim was Nebuchadnezzar’s puppet now.

The Judean kings were restless under Babylonian rule. In 598 B.C.E. the Babylonians laid siege to Jerusalem to squelch Jehoiakim’s rebellion. He died before the Babylonians succeeded in taking the city. But in 597 B.C.E., his son Jehoiachin and many of Judah’s citizens, including the prophet Ezekiel, were taken into exile for their insurrection (2Kgs 24:12-16). Nebuchadnezzar appointed Zedekiah, another son of Josiah, as king. He, too, rebelled against his Babylonian master; the Babylonian army laid siege to Jerusalem again, and in 586 B.C.E. the Babylonians destroyed the city, leveled its temple, and exiled many of its people to Babylonia (2Kgs 25; Jer 52).

From the Babylonian perspective, the destruction of Jerusalem was necessary to maintain the imperial political order.

Bibliography

- Leick, Gwendolyn, ed. The Babylonian World. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Oates, Joan. Babylon. Revised edition. London: Thames & Hudson, 1986.

- David M. Carr, “Source Criticism,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation, ed. Steven L. McKenzie (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 2:318-26. Lenzi, Alan. “Assyriology: Its Importance for Biblical Interpretation.” In Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Edited by Steven MacKenzie. New York: Oxford University Press. 2013.