The book of Jeremiah takes pains to depict Jeremiah as a legitimate prophet of the Israelite god, Yahweh. In Jeremiah’s time, Judah was a nation divided over foreign policy and religion, and prophets with opposing messages claimed to speak for Yahweh (Jer 28). According to the book of Jeremiah (our only source of information about him), it was Jeremiah’s determination to preach the word of Yahweh despite opposition that established his authenticity. He forcefully asserts the truth of his denunciatory prophecies against the optimistic predictions of other prophets, whom he accuses of prophesying lies (Jer 23:9-40).

Yahweh designates Jeremiah a “prophet to the nations” (Jer 46-51) and commissions him to pronounce judgment against not only Judah but also other nations: “See, today I appoint you over nations and over kingdoms, to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant” (Jer 1:10).

When appointed, Jeremiah, like many biblical figures, professes his unworthiness. As Moses claims to be “slow of speech and slow of tongue” (Exod 4:10), so Jeremiah exclaims, “I do not know how to speak, for I am only a boy” (Jer 1:6). Because Jeremiah’s prophetic career might have spanned as much as 40 years, he may indeed have begun prophesying while young (Jer 1:2-3). But like other biblical figures, Yahweh promises to help him overcome his inadequacies and his opponents (Jer 1:7-9).

Jeremiah warns that Yahweh will bring disaster on Judah because the people rebelled against Yahweh by worshipping other gods, by pursuing policies hostile to Babylon, whose dominion Yahweh had ordained, and by allowing widespread social injustice (Jer 22:8-9).

Jeremiah’s condemnatory prophecies and his pro-Babylonian stance earn him many enemies. Some ridicule him and others even plot against his life (in his own hometown of Anathoth, no less; Jer 11:18-23). Jeremiah is beaten and imprisoned and his writings are destroyed (Jer 20:1-6, Jer 36:20-26, Jer 37:11-16). He narrowly escapes death at the hands of a mob of religious officials and other prophets (Jer 26). Jeremiah’s perilous career places him in the company of several other biblical prophets (Jer 26:20-23), and his willingness to prophesy despite antagonism is poignantly highlighted in several passages, sometimes called the Confessions of Jeremiah, in which he laments his persecution, often in the style of the Psalms.

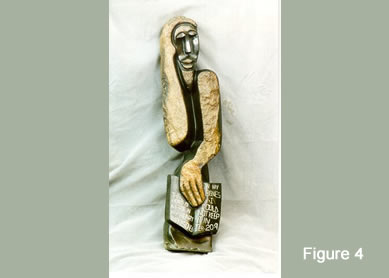

A public showdown between Jeremiah and Hananiah, a rival prophet, dramatizes the battle over true prophecy (Jer 27-28). Using a wooden yoke around his neck as a prop, Jeremiah tells his audience at the Jerusalem temple that Judah must submit to Babylon to survive. But Hananiah, who seizes Jeremiah’s yoke and smashes it, counters that Yahweh has broken the “yoke” (that is, the “power”) of Babylon and will restore Judah’s fortunes in two years. The confrontation with Hananiah is just one example of Jeremiah’s dramatic use of props, symbolic acts, public performances, and other forms of “guerilla theater” to convey the divine word (see, e.g. Jer 19).

Though Jeremiah stresses that Yahweh will “pull down” and “pluck up,” he also shows that Yahweh will “build” and “plant.” Calls to repentance and promises of deliverance often dot Jeremiah’s warnings. Additionally, the book contains two chapters, appropriately known as the Book of Comfort, devoted to the promises of a new covenant and restoration (Jer 30-31).