Alexandria was the second-most important city in the Roman Empire, after Rome itself. It was named for its founder, Alexander the Great, who built the city after his conquest of Egypt (331 B.C.E.) in order to facilitate naval trade and communication with Greece. It soon became the political capital of Egypt and a center of Hellenistic culture, featuring one of the greatest libraries of the ancient world. During the Roman period (30 B.C.E. onward), the city also featured one of the largest Jewish communities in the Mediterranean and is traditionally believed to be the place where the Septuagint (ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures) was produced.

How did the Hellenistic culture of Alexandria influence the Bible?

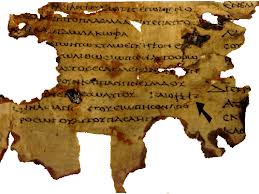

In the later Hellenistic and Roman periods, large numbers of Jews were living outside the traditional Jewish homeland as part of the Diaspora. For many of them, Greek was the everyday language, not Hebrew, so the original biblical text was less accessible.

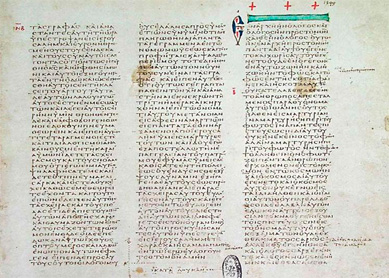

Some time in the third century BCE, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures (initially just the Torah) was begun in Alexandria. The pseudonymous Letter of Aristeas credits this work to 72 (or 70) translators, but the text actually took shape over several centuries. Some details in the translation seem to reveal the Hellenistic, urban context of the translators, in contrast to the earlier contexts of the Hebrew texts. For example, into the diatribe against the king of Babylon in Isa 14 translators inserted references to Antiochus IV Epiphanes (ruled 175-164 B.C.E.), the Seleucid king who had suppressed traditional Jewish practices and installed a Gentile as high priest in the temple.

Similarly, in Deuteronomy geographical references are updated, and Moses at one point tells the people to “return to your houses” (Deut 5:30, NETS), instead of “return to your tents” as in the Hebrew text. Attempts by scholars to demonstrate systematic, ideologically motivated changes in the Septuagint, however, are difficult to support based on the evidence. Alexandrian Jews immediately received this translation as having full authority and condemned anyone who would try to alter it, and there is no question about its impact on Diaspora Jews. The Jewish interpreter Philo of Alexandria (circa 20 B.C.E.-50 C.E.) used this Greek version exclusively in his commentaries, and he expanded the legend in the Letter of Aristeas by claiming that the 72 translators had worked independently but produced identical Greek translations (Moses 2.25-44).

By the time of Jesus, the entirety of the Hebrew Scriptures was translated and widely read in Greek. In fact, the authors of the New Testament typically quote from and interpret the Hebrew Scriptures in their Greek forms, not their Hebrew forms. This impacts the Gospels, for Jesus is often presented as quoting the Septuagint version, even when it differs from the Hebrew text. Paul also displays a preference for the Greek text of the Hebrew Scriptures in his letters. Thus, for most early Christians, their “Old Testament” was the Septuagint.

Later, it was an Alexandrian scholar, the Christian writer Origen (circa 185-254 CE), who united the Hebrew and Greek texts into a single edition called the Hexapla, which listed a Hebrew text and several Greek translations in parallel columns. It is unknown why Origen undertook this project. Could it have served a polemical function in debates with Jewish authors? Or did he simply desire to work out a “best text” for his own sermons and commentaries? Either way, the Hexapla is significant as an early attempt to perform textual criticism.

How did thinkers from Alexandria shape biblical interpretation?

Just as Jews in Alexandria were influenced by the Greek language, they were also influenced by Greek philosophy. Some Greek philosophers and grammarians used a method of literary interpretation called allegory to defend or explain problematic accounts in Homer’s epics. According to these philosophers, these troublesome passages should be read symbolically, not literally.

In Alexandria, Philo applied this method to interpreting the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. He produced numerous allegorical commentaries on the Pentateuch, with particular emphasis on Genesis and Exodus. Philo’s method influenced early Christian commentators such as Clement (circa 150-215 C.E.) and Origen. Origen, for example, proposed that scripture may have three levels of meaning: literal, moral, and allegorical. When the literal reading of a passage is problematic, this was a sign to Origen that an enlightened reader must seek a deeper, symbolic meaning. Only the “simple” remain mired in literalistic readings, he thought. Origen’s method reveals that for ancient readers, like for us today, some biblical passages resist easy interpretation.

Bibliography

- Dawson, David. Allegorical Readers and Cultural Revision in Ancient Alexandria. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- Vrettos, Theodore. Alexandria: City of the Western Mind. New York: Free Press, 2001.

- Niehoff, Maren R. Jewish Exegesis and Homeric Scholarship in Alexandria. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Trigg, Joseph W. Origen. New York: Routledge, 1998.

- Law, Timothy Michael. When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.