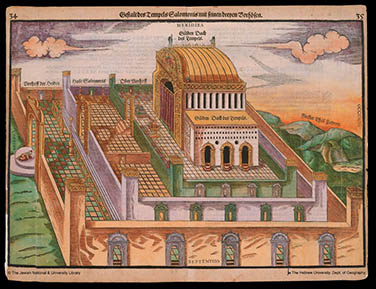

There is an Arabic saying that “the multitude of names proves the excellence of the bearer.” Islamic tradition has adorned Jerusalem with 17 names. Jerusalem’s significance in the Hebrew Bible is clear from the several images used to speak of the city. Though not all are flattering, they do point to Jerusalem’s unique status.

Among the most frequently occurring images of Jerusalem is “the holy mountain.” It appears 25 times in the psalms and several prophetic books (e.g.,

Another frequently occurring image speaks of Jerusalem as “daughter Zion.” The origins of this female metaphor are not entirely clear. Still, describing the city as God’s daughter implies familial intimacy. “Daughter Zion” and its people are often depicted as victorious, secure, and prosperous (e.g.,

Several other feminine images used for Jerusalem are unflattering, pointing to the people’s infidelity to their God: the adulteress (

Because the Hebrew Bible affirms that judgment is not God’s last word to Judah, more positive feminine images appear as the prophets speak about Jerusalem’s restoration. The city will no longer be called “Forsaken” and “Desolate” but “My Delight” and “Espoused” (

An image of Jerusalem unique to the book of Isaiah calls the city “Ariel” (

Both the positive and negative images for Jerusalem underscore the city’s significance for the people of ancient Israel. The most important image of all, however, is Jerusalem as a “holy” city (

Bibliography

- Maier, Christl M. Daughter Zion, Mother Zion. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2008.

- Hoppe, Leslie J. The Holy City: Jerusalem in the Theology of the Old Testament. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2000.

- Levine, Lee I. Jerusalem: Its Sanctity and Centrality to Judaism, Christianity and Islam. New York: Continuum, 1997.